In the autumn of 1943, the winds sweeping across the Minnesota prairies carried more than just the scent of turning leaves and damp earth. They carried the sounds of a foreign tongue—German and Italian—drifting from the back of flatbed trucks and across the endless rows of potato bogs and cornfields. For the residents of small-town Minnesota, the war was no longer a distant headline from the European or Pacific theaters. The war had arrived at their doorstep, dressed in surplus uniforms marked with a bold, stenciled “PW.”

Today, the story of the Prisoner of War (POW) camps in Minnesota is a fading echo, a footnote in the grand narrative of the “Greatest Generation.” Yet, for a brief, surreal window between 1943 and 1946, the state became the caretaker of its own enemies. It was a social experiment born of desperation, governed by the strictures of the Geneva Convention, and defined by a thousand small acts of unexpected decency that would eventually change the lives of thousands of men on both sides of the barbed wire.

🧭 I. The Empty Liberty Ships

The genesis of the Minnesota POW experience was rooted in a logistical crisis. By 1943, the British government was drowning in captives. Following the surrender of the German Afrika Korps in North Africa, over 200,000 soldiers were sitting in desert camps with no infrastructure to support them. Mainland Europe was under Nazi occupation, and Great Britain was already rationed to the brink.

The solution was found in the “Liberty-class” cargo ships. These vessels were crossing the Atlantic to drop off war supplies for the invasions of Sicily and Italy, but they were returning to the United States empty. To maximize efficiency, the U.S. military began filling these return voyages with human cargo.

“We had no beds on the ship,” recalled one German veteran. “Every one of us got a blanket and a life jacket.” They arrived in New York and were immediately funneled onto trains heading west. As the locomotives chugged through the American heartland, some German prisoners, still fueled by Nazi propaganda, threw leaflets out the windows, warning American citizens that the Third Reich was unstoppable and that they were on the losing side of history. They had no idea they were heading toward a landscape that would dismantle their ideology, not with bullets, but with bread.

🔍 II. The High Road: The Geneva Convention in Practice

When the first wave of 3,000 prisoners arrived, the United States faced a moral and strategic crossroads: How do you treat the man who was trying to kill your son yesterday?

The decision was made to adhere strictly to the Geneva Convention of 1929. This wasn’t merely a humanitarian gesture; it was a cold, calculated military strategy. The U.S. knew that if word reached the front lines that prisoners were being well-treated—fed the same rations as American soldiers, provided with medical care, and given clean housing—German soldiers would be far more likely to surrender.

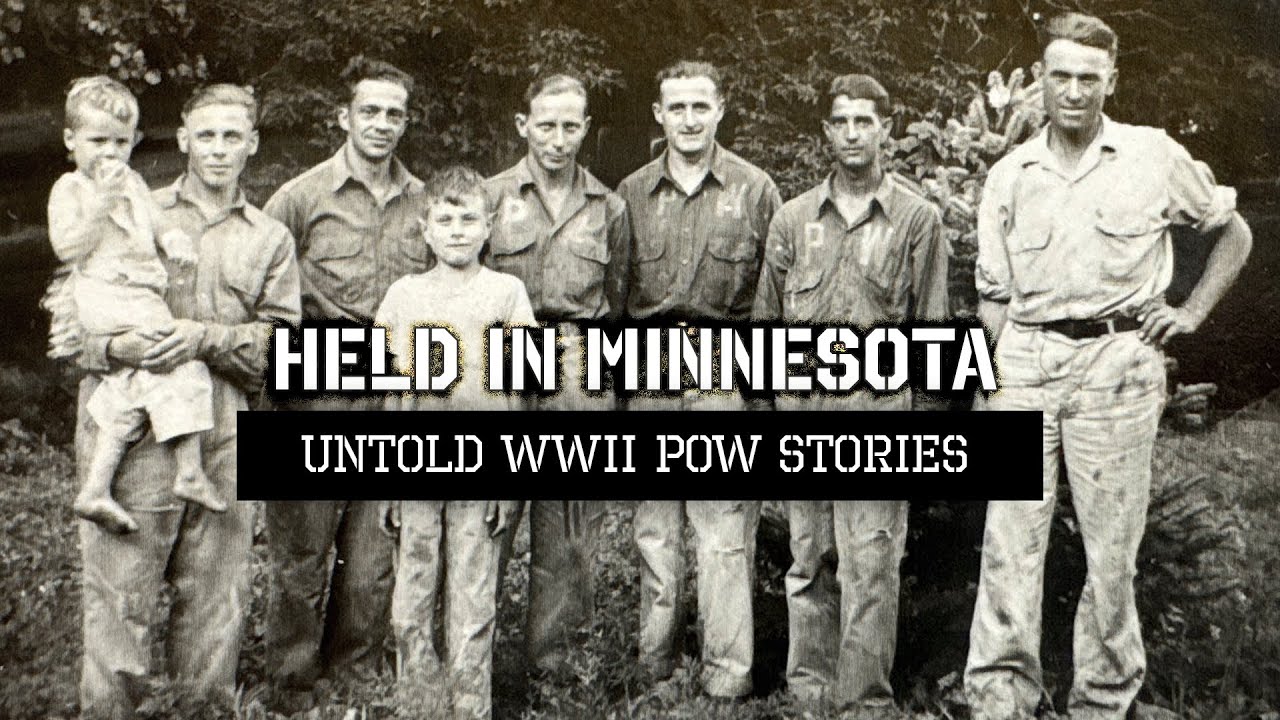

In Minnesota, this “High Road” was paved with meticulous detail. Prisoners were given World War I-era uniforms with “P” and “W” painted on the back. They were processed, interviewed, and sent to “base camps” like the massive facility in Algona, Iowa, which served as the administrative hub for the branch camps scattered across the North Star State. From Owatonna to New Ulm, and from Moorhead to the logging camps of Bena, the “enemy” became an integral part of the local economy.

🌾 III. The Agricultural Necessity

The timing of the prisoners’ arrival was providential for Minnesota’s economy. The state was facing a catastrophic labor shortage. The National Guard units had been called up years earlier, and the young men who usually manned the canning factories and harvest crews were fighting in the hedgerows of France or the jungles of Guadalcanal.

Agricultural Extension officers realized that without help, the crops would rot in the fields. In Princeton, Minnesota, O.J. Odegard, a titan of the local potato and onion industry, became one of the first to utilize POW labor. The “Nordic stock” of Minnesota—Germans, Norwegians, and Swedes—suddenly found themselves face-to-face with Mediterranean men.

“Folks in these parts had not seen a lot of Mediterranean men before,” one local historian noted. The Italians, in particular, left a vivid impression. They were known for their singing, their voices echoing from the trucks as they were driven to the bogs. Odegard set the tone by being more than decent; he was respectful. He set up a canteen where they could buy beer and cigarettes, and he paid the government the going rate for field help—$3 a day—ensuring the prisoners were treated as workers, not slaves.

🎨 IV. The Rehabilitation of Humanity

In Owatonna, the POW experience took on a more philosophical dimension. The camp was located on the vacant Thomas Cashman farm, and its success was largely due to the oversight of Howard Hong, a St. Olaf College professor working with the YMCA.

Hong understood that for these men, the greatest enemy wasn’t the American soldier, but the vacuum of their own minds. Under the Geneva Convention, he facilitated education, art, and music. The University of Minnesota even set up correspondence courses for the prisoners.

“One of the prisoners said the best thing that happened to him in the war was that it made him aware that he could be rehabilitated, or he could gain his humanity back,” a researcher explained. In the recreation rooms, prisoners formed bands, played chess, and read the New York Times (translated into German). They were being exposed to the “flavor of democracy,” a stark contrast to the rigid, fear-based indoctrination they had lived under since Hitler took power in 1933.

⚡ V. The Friction of the “Hardcore”

However, the camps were not without tension. The makeup of the prisoner population was a volatile mix. The early arrivals from the Afrika Korps were often “hardcore” nationalists who still believed in a German victory. When the second wave arrived after D-Day—men who had seen the collapse of the German war machine firsthand—friction emerged.

In some camps, the fanatical Nazis established internal “kangaroo courts,” threatening and even killing those they deemed “traitors” or “defeatists.” The word Verräter (traitor) became a death sentence.

This led to the creation of unique “safe” camps, such as the one in Howard Lake, Minnesota. This facility was populated entirely by prisoners who had been threatened by their own comrades at the base camps. The American commanders used the Minnesota branch system to separate the disillusioned from the fanatical, providing a sanctuary for those who had seen through the Nazi myth.

🍺 VI. Rule-Bending and the Black Lab

As the months passed, the line between “enemy” and “neighbor” began to blur. In New Ulm, a town with deep German roots, the prisoners often spoke the same dialect as the local farmers. It was not uncommon for a farmer to pick up a work crew, drive them to the farm, and invite them to sit at the family dinner table.

“My husband would go to the camp, fill out the paperwork, and bring them to the farm,” one local woman recalled. “They would come with a paper bag of sandwiches, but we knew nobody could do a good day’s work on just sandwiches. We fed them like a threshing crew.”

There were stories of “rule-bending” that would have horrified the high command in Washington. In Moorhead, a farmer named Hank Peterson became so fond of his workers that he took them into a downtown bar for beers. In another instance, a group of prisoners painting a barn in Moorhead decided to play a prank on the farmer’s eight-year-old son. They took his black Lab and painted a white stripe down its back so it looked like a skunk. “They thought it was so funny,” the son recalled decades later. “I didn’t think it was so funny at the time, but it showed they were just guys, just kids.”

💔 VII. The Shadow of the Atrocities

The atmosphere of the camps shifted dramatically in 1945. As the war in Europe ended, the full extent of the Nazi atrocities and the Holocaust became public knowledge. The “jolly” relationships between the townsfolk and the prisoners were suddenly complicated by the horrifying images coming out of Buchenwald and Dachau.

The prisoners, too, were forced to reckon with the reality of their government. For many, the transition from being a soldier of the Reich to a witness of its crimes was a crushing psychological blow. Yet, the American policy remained steadfast: the prisoners were to be repatriated according to the law. By 1946, the camps were emptied, and the men were sent back to a Europe that lay in rubble.

🕊️ VIII. The Enduring Legacy: “Mercy Outlasts Victory”

The story of Minnesota’s POWs did not end with the closing of the gates. For many Germans and Italians, the time spent in the Midwest was “the best time of their lives.” They went back to Europe as ambassadors of democracy. They had seen that a society could be productive without being a police state; they had seen that an enemy could be treated with respect.

Decades later, letters began arriving in small Minnesota towns. “I worked for you in 1944… you treated me so well,” one letter read. Another prisoner, Alfred Mueller, was so moved by his treatment that he moved his entire family back to Minnesota after the war, eventually becoming a U.S. citizen. He even donated $1,500 to the Camp Algona museum to ensure the story of American decency was never forgotten.

The most poignant memory of the era comes from a woman named Marlene, who was eight years old when the Italian prisoners arrived in Princeton. She recalled the crowd standing back in fear, having been told these men were “vicious monsters.”

Suddenly, a three-year-old girl broke loose from her mother’s grasp, ran across the platform, and hugged the leg of an Italian soldier. The crowd gasped, terrified of what the “monster” would do. The soldier didn’t strike her. He didn’t move away. He picked the little girl up and began to weep.

In that moment, the war ended for everyone on that platform. It was a reaffirmation of a basic truth that the Minnesota POW camps proved to the world: that even in the darkest hours of human history, decency is a choice. And it is a choice that has the power to turn an enemy into a friend, and a prisoner into a man again.

News

The Coca-Cola at the Edge of Death

They arrived without a word, without an explanation, and without the smallest hint of what awaited them. The silence was so thick it felt unnatural, pressing against…

THE NIGHT THE ENEMY GAVE HIS COAT

December 15, 1944 – Bavaria, Germany The cold arrived like a weapon. At just twelve degrees Fahrenheit, the air outside Munich cut through flesh and bone with…

Inside One of the Most Compelling Bigfoot Evidence Trails Ever Documented

In the ongoing debate over the existence of Bigfoot, few forms of evidence have generated as much fascination—and controversy—as footprints. Blurry photographs and fleeting sightings can be…

Footprints in the Dark: When the Wilderness Fought Back

For centuries, legends have warned that the wilderness is not empty. That beyond the reach of roads, cell towers, and human certainty, something else still moves. Something…

Whispers in the Wilderness: The Search for Bigfoot

Across America and beyond, tales of an elusive man-like creature known as Bigfoot or Sasquatch have captivated the imagination of many. Thousands of reports, photos, and videos…

End of content

No more pages to load