October 1943, the European sky was eating men.

Over Germany, B‑17 Flying Fortresses crawled home in broken strings—engines coughing smoke, wings torn open like fabric, gunners staring at empty positions where friends had been minutes earlier. The formations that returned looked less like victory and more like evidence: daylight bombing, the proud American promise, was turning into a public execution carried out at 30,000 feet.

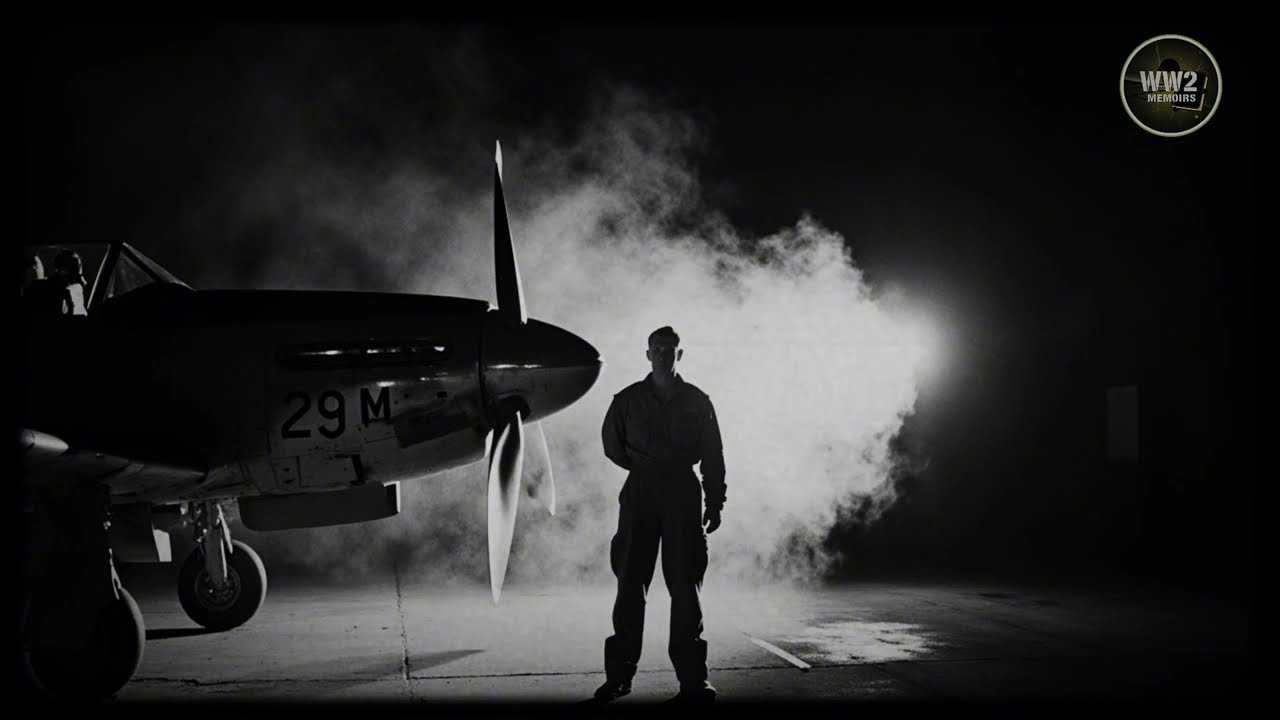

And on that same day—half a world away, far from flak and contrails—one fighter sat forgotten on a quiet airfield, coated in dust like something already retired. It was sleek, almost elegant, the kind of shape that suggested speed even while standing still. But the sign on its fuselage told a different story in blunt bureaucratic ink:

REJECTED — UNSUITABLE FOR HIGH-ALTITUDE OPERATIONS.

To most men, that sign was a full stop. To one man, it was a dare.

His name was Ronald Harker, a 30-year-old Rolls‑Royce test pilot and engine specialist. He wasn’t a general. He wasn’t a famous designer. He didn’t command squadrons or sign procurement orders. He lived in the space where machines either worked or killed the people who trusted them. And in the autumn of 1943, the war over Europe was hanging by a thread woven from fuel limits, committee delays, and the cold arithmetic of missing crews.

The Americans were pushing deeper into Germany every week. Their escort fighters—the P‑47 Thunderbolt and P‑38 Lightning—could fight brilliantly, but only for so long. Beyond a certain radius, the escorts had to turn back, and the bombers were left alone, slow and predictable, flying straight into waiting packs of Messerschmitts and Focke‑Wulfs.

The Luftwaffe understood that gap in the sky the way wolves understand a fence line: once the guard dogs go home, the herd belongs to you.

Reports from the Eighth Air Force were brutal. On the worst days, hundreds of airmen vanished in a single raid. A bomber group was supposed to finish twenty-five missions before its men could rotate home. By late 1943, crews didn’t count missions anymore—they counted the odds. The average life expectancy of a bomber crew felt closer to a gambler’s streak than a military plan.

Inside offices filled with charts and cigarettes, committees produced solutions that died on paper. Drop tanks, revised formations, tactical adjustments—each one improved margins but didn’t break the fundamental problem:

The bombers needed a fighter that could stay with them to Berlin and back.

And in one corner of British air operations, a plane that had been written off as mediocre sat quietly waiting for someone stubborn enough to see past its label.

A Perfect Body with the Wrong Heart

The aircraft was the P‑51 Mustang, built by North American Aviation. On paper, it had been dismissed as a low-altitude machine—good for reconnaissance, fast down low, but crippled where the air grew thin. Its American-built Allison engine simply couldn’t breathe above roughly 15,000 feet. The test results were disappointing enough that procurement officers, satisfied they’d seen all they needed, began to move on.

In war, being “good enough for a minor role” can be a slow death sentence. Projects that aren’t urgently needed get buried under louder demands. The Mustang had become an orphan—admired for its aerodynamics, doubted for its altitude performance, and ultimately shelved because it did not solve the crisis that mattered most.

But Harker’s mind worked like an engineer’s and a pilot’s at once. He didn’t look at the Mustang and see a failure. He saw a mismatch.

The problem, he believed, wasn’t the airframe.

It was the heartbeat inside it.

Harker had spent years testing the Rolls‑Royce Merlin, the engine that powered Britain’s finest aircraft. The Merlin didn’t merely run at high altitude—it lived there. Its supercharging system fed it air when lesser engines began to choke. It gave aircraft the ability to fight above 30,000 feet, where the cold could freeze breath inside masks and the sky became a place of slow, lethal geometry.

If the Mustang’s body was as clean and efficient as its admirers whispered, and if the Merlin could give it lungs, then the combined machine wouldn’t be a minor improvement.

It would be a new species.

The problem was that nobody had asked Harker’s opinion. And acting on it would be, in every official sense that mattered, unauthorized.

Wartime procedure was strict for a reason. Aircraft were property, contracts were binding, and allies still operated with walls of protocol between them. A Rolls‑Royce specialist did not get to casually recommend—let alone execute—major modifications to an American design without approvals, committees, and months of paper. In October 1943, months were measured in funerals.

Harker saw that. And once a man sees the gap between what must be done and what is permitted, the war begins inside him.

The Slaughter in the Gap

The Eighth Air Force’s daylight offensive was built on the idea that precision bombing could cripple German industry without flattening German cities. But precision required visibility, and visibility meant flying predictable routes at predictable altitudes—perfect conditions for German interception.

German radar tracked American formations almost the moment they crossed into hostile airspace. Fighter control stations vectored packs of interceptors into the bomber streams, timing attacks for maximum damage. The Luftwaffe didn’t need to win forever; it only needed to keep killing faster than America could replace trained bomber crews.

The American escorts fought hard, but fuel dictated their courage. A P‑47 could climb high and dive like a meteor, but its range was limited. The P‑38 was deadly in the right conditions, yet it struggled in Europe’s cold, and reliability issues haunted its long missions.

Targets like Leipzig, Regensburg, and Berlin lay beyond safe escort range. Every commander knew what happened at the edge of that range: the escorts peeled away, and German fighters surged in.

Bomber gunners watched the escort fighters turn back and felt something close to abandonment. The Germans attacked with confidence then—not always because they were braver, but because they were finally attacking a prey animal without teeth.

“Unsustainable” doesn’t capture what it felt like to fly those missions. Unsustainable is a budget problem. This was a human one.

And it was in that context—men dying because the system moved too slowly—that Harker looked at a rejected Mustang and decided the rules were no longer sacred.

Duxford: The Flight That Lit the Fuse

April 30, 1943, RAF Duxford. Spring rain and oil hung in the air. Mustangs sat along the field streaked with mud from low-level work over occupied France. They were fast and agile down low. But every pilot on the base knew the bitter truth: if the fight moved higher, the Allison engine faltered.

Harker arrived officially to study engine wear. Unofficially, he came with a question sharp enough to cut his career in half.

Could the perfect airframe be saved?

A squadron commander, half amused, offered him a flight. “Go on,” the man said, as if handing a civilian the keys to disappointment. “Just don’t expect miracles.”

Harker climbed into the cockpit and pushed the throttle forward. The Mustang lifted cleanly, smooth as a bird released from a cage. At 15,000 feet, the Allison began to gasp exactly as the pilots had warned. But what struck Harker wasn’t the weakness.

It was everything else.

The aircraft felt right—balanced, responsive, efficient. The laminar-flow wing cut through air with astonishing ease. The fuselage offered speed with minimal drag. It was, in his hands, the kind of design you wanted to protect with your life—because it could protect others.

He descended through cloud and rain with a dangerous clarity settling into him: this wasn’t a bad airplane.

It was a great airplane trapped behind a weak engine.

By the time he landed, he knew what he would recommend.

And he also knew he was not allowed to recommend it.

Within seventy-two hours, Harker typed a detailed report addressed to Air Vice-Marshal Sir Wilfrid Freeman. He wrote in the language of engineering—calm, precise, damning. And near the beginning, he committed the kind of bureaucratic sin that can end careers:

“The Mustang airframe is superior to any fighter currently in production.”

He went further: install a Merlin 61 and the result would exceed existing operational fighters in high-altitude performance and range.

It was an illegal recommendation by wartime standards—foreign property, foreign chains of command, official channels bypassed. But Freeman read it twice and sent it onward with a note that sounded like quiet rebellion disguised as duty:

Proceed—regardless of diplomatic complications.

In war, permission sometimes arrives wearing a different name. In this case, it arrived as a senior official willing to accept the risk because he could see the price of hesitation.

Conversion X: Engineering as Mutiny

At Rolls‑Royce’s Hucknall facility, engineers pulled one Mustang—serial AL975—into a corner of the hangar. Official records would later refer to it only as “Conversion X.” No fanfare. No press. No public observers. Only a handful of men, working with the tense awareness that their project could be seen as theft if the wrong person asked the wrong question.

They stripped out the Allison engine and began the mechanical work of heresy: adapting the Mustang’s mounts for the larger Merlin, redesigning cooling systems, reshaping the cowling, fitting a four-bladed propeller to handle the extra torque. There were no approved blueprints. Every adjustment was improvised with measurements, trial fits, and engineer’s instinct.

They worked after hours. They worked when nobody was supposed to be watching. They worked with the intensity of men who understood the difference between a violation of protocol and a failure of morality.

Every day the European sky demanded proof.

By October 1943, after months of secret labor, the hybrid aircraft rolled out into pale autumn light. The British called it Mustang X. Under its smooth cowling purred the heart of a Spitfire.

Harker climbed into the cockpit, strapped in, and advanced the throttle. The Merlin roared to life with a deeper, sharper confidence than the Allison’s strained cough. The propwash threw dust across the field as the aircraft surged forward.

The Mustang lifted cleanly and climbed faster than any Mustang had climbed before.

At 25,000 feet, Harker pushed the throttle open and watched the airspeed needle run—400… 410… 430 miles per hour. The controls remained steady and alive, the aircraft responsive in a way that made the numbers feel less like data and more like destiny.

When he landed, he wrote a sentence in his logbook that would ricochet through two air forces:

“The Merlin Mustang is the finest fighter aircraft I have ever flown.”

The Fight with Pride—and the Collapse of Doubt

British pilots who flew the Mustang X came back with eyes that looked newly awake. They described an aircraft faster than expected, higher than expected, and—most importantly—capable of escort range that changed the map.

Across the Atlantic, the first American reaction was skepticism. Procurement memos were polite but cold: the RAF’s suggestion was “noted,” but allocating resources to modify a previously rejected design was “not efficient.”

It wasn’t purely technical doubt. It was also pride. Admitting the British had improved an American aircraft was politically uncomfortable. Bureaucracies do not like being proven wrong in public, and they like it even less in wartime.

But Freeman—and the men who had already broken the seal—played the next card with the calm ruthlessness of someone who understands systems. Rolls‑Royce’s American licensee, Packard, was already building Merlins in Detroit. So the engine could be framed not as a foreign transplant, but as an American-built solution.

By the time Washington fully grasped what was happening, the experiment had become a moving object. And in wartime, moving objects acquire momentum faster than paper can stop them.

North American Aviation completed prototype conversions. Test pilots reported what Harker already knew: exceptional performance, stable handling, speed, altitude—and range.

The converted aircraft became the P‑51B.

And suddenly, in the language commanders understood best, the arithmetic changed.

Here was a fighter that could escort bombers deep into Germany. With external tanks, it could go the distance that had been killing crews. It meant that for the first time, the Luftwaffe could be met not just near the coast, not just at the edge of the battle, but over the targets that mattered—over Berlin’s heartland.

General Henry “Hap” Arnold read the data and issued a directive that turned the forbidden into official doctrine:

Convert P‑51 production to Merlin configuration immediately.

The system that had resisted innovation now devoured it at full speed, because once the numbers prove something, a military bureaucracy can change with startling violence.

Factories shifted. Production lines reoriented. By spring 1944, Mustangs were arriving in England in meaningful numbers. Pilots who had flown P‑47s and P‑38s climbed into the new aircraft and felt, almost instantly, that the war had tilted.

When the Bombers Stopped Flying Alone

Bomber crews learned the Mustang’s silhouette the way sailors learn the outline of a lighthouse. The sleek, long-nosed fighters glinting above the formation did more than comfort them. They rewired expectation.

Before, escort meant borrowed time. Now escort meant presence—deep, constant, faithful.

When the Luftwaffe appeared, the Mustangs could dive into them with speed and precision and still have fuel to return. They weren’t forced to turn back at the edge of Germany like men apologizing. They stayed. They hunted.

That shift mattered in ways that statistics can’t fully capture. Air war is not only machines and kill ratios. It is morale. It is the human willingness to keep climbing into a cockpit knowing the odds.

The Mustang altered that psychology. Bomber crews began believing they could survive long enough for strategy to matter. Fighter pilots began believing they could not only defend but destroy the German fighter force as a system.

And the Eighth Air Force’s doctrine changed accordingly. Under new leadership, fighters were no longer chained to a defensive orbit around bombers. The mission widened: destroy the German air force wherever found—in the air, on the ground, and in the factory chain that produced it.

The Mustang made that possible because it gave pilots the most precious commodity in the sky:

time.

Time to escort. Time to chase. Time to sweep ahead. Time to fight and still come home.

A Machine That Was Also a Verdict

The P‑51’s rise is often told as inevitability—an obvious outcome once the “right engine” was installed. But nothing about it was inevitable in the moment it mattered.

In the moment, it was a rejected aircraft sitting under dust. It was a bureaucracy focused on reliability, not risk. It was committees delaying decisions while bombers burned. It was national pride resisting the embarrassment of being corrected.

And it was one man—Harker—choosing to treat a regulation like a suggestion because he understood what regulations cannot measure: the value of lives that would be lost while paperwork moved.

That is what makes the Mustang story a wartime drama rather than an engineering anecdote. The Mustang was not rescued by a board meeting. It was rescued by a man in a cockpit who recognized a good airframe suffocating, and by engineers in a hangar who worked like conspirators because they believed the machine could change the war.

By 1945, the Merlin-powered Mustang had become a symbol of Allied air supremacy. Thousands of bomber crews owed their survival to fighters that did not abandon them at the edge of range. German pilots learned to fear the sound and sight of a plane that could meet them anywhere and stay long enough to finish the fight.

Yet beneath the legend, the origin remained what it had always been:

A forbidden idea.

A rule broken on purpose.

A flight taken because obedience had become too expensive.

History likes to assign victories to generals and grand strategies. But sometimes the turning point is smaller and sharper: a mechanic’s stubbornness, a test pilot’s eye, an engineer’s refusal to accept a stamped verdict of failure.

In October 1943, when bombers were dying in the gap, a rejected Mustang waited under dust. Ronald Harker looked at it, ignored the label, and chose to gamble his career against the slaughter in the sky.

The roar that followed wasn’t only horsepower.

It was innovation taking flight.

News

The Coca-Cola at the Edge of Death

They arrived without a word, without an explanation, and without the smallest hint of what awaited them. The silence was so thick it felt unnatural, pressing against…

THE NIGHT THE ENEMY GAVE HIS COAT

December 15, 1944 – Bavaria, Germany The cold arrived like a weapon. At just twelve degrees Fahrenheit, the air outside Munich cut through flesh and bone with…

Inside One of the Most Compelling Bigfoot Evidence Trails Ever Documented

In the ongoing debate over the existence of Bigfoot, few forms of evidence have generated as much fascination—and controversy—as footprints. Blurry photographs and fleeting sightings can be…

Footprints in the Dark: When the Wilderness Fought Back

For centuries, legends have warned that the wilderness is not empty. That beyond the reach of roads, cell towers, and human certainty, something else still moves. Something…

Whispers in the Wilderness: The Search for Bigfoot

Across America and beyond, tales of an elusive man-like creature known as Bigfoot or Sasquatch have captivated the imagination of many. Thousands of reports, photos, and videos…

End of content

No more pages to load