This is not a story about a monster in a swamp, not in the way people mean it when they lean closer and ask for teeth and scales and a name they can repeat in the dark. This is a story about a man who did what he had done for decades—went out on the water before dawn, worked his nets with a steady hand, trusted the bayou the way working people trust the roads they travel every day—and never returned.

It is also a story about three witnesses who still live within a couple of miles of that canal, men who can point to the bend where the water changed. None of them has ever been able to explain what surfaced from the murk at the moment Raymond Boso disappeared before their eyes.

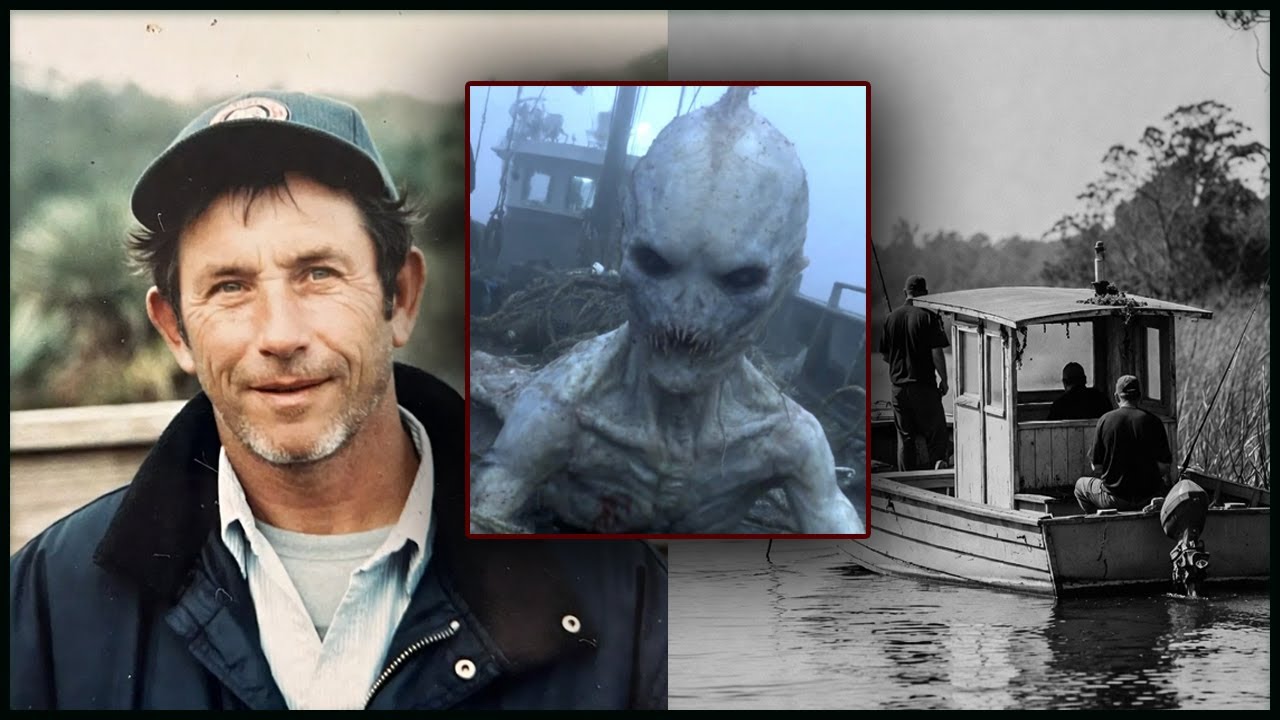

Raymond was fifty-one in June of 1996, typical of the parishes along the Louisiana coast: the son of a fisherman, a fisherman himself, a man whose plans did not reach farther than the next season. He didn’t talk about getting rich. He talked about making it to retirement as long as his motors and his back held out. He lived in Lafourche Parish but worked a few hours away in the Bayou Bianu swampy canal system, where the water was shallow, the shoreline monotonous, and the work did not care whether you were tired or not.

That summer wasn’t going well. The water ran warm but the catch kept falling. Men argued about pollution, about changing currents, about big trawlers taking too much. None of the talk changed the fact that mornings still began the same way: leaving before dawn, running several trips, returning by lunchtime to unload shrimp and small fish at the pier. When the sea—and the bayou—refused to give, men like Raymond made do by working harder and sleeping less.

The morning he vanished started like any other.

A small motorboat with low sides. An old two-stroke engine that coughed before it caught. Nets stacked in rough piles, boxes ready for the haul. Four people aboard: Raymond, his two cousins, and a younger man who had joined the crew recently, still learning which silences meant “pay attention” and which meant “just keep working.”

They left while the air was barely tolerable, a thin fog laying over the water like breath on glass. There was almost no wind. The canal carried them forward through a landscape that never tried to be pretty: murky stagnant channels overgrown with reeds and cypress, silt ridges along the edges, snags waiting at the bottom. In that part of Bayou Bianu the depth averaged four to eight feet and dipped less in places—shallow enough that old timers liked it. Shallow meant predictable. Shallow meant you didn’t have to fear what lived far beneath you.

The water itself was opaque, brownish, smelling of silt and rotting plants. You couldn’t see your own hand beneath the surface. You learned to read the bayou the way you read a person’s face—by surface cues, by ripples, by motion where motion shouldn’t be. Alligators were part of the landscape. Locals were calm about them. They knew where gators liked to bask, how to keep your hands out of the water, how not to clean fish at the edge like an invitation.

That was the deal. Respect the bayou, and the bayou would leave you alone.

By a little after four in the morning, they had already set several nets and were heading toward the next spot—one they’d known a long time and considered theirs. Fewer strangers went out there, fewer other boats, better chances for a decent catch.

Raymond stood closer to the stern, holding one net in his hands, ready to throw on command. One cousin worked the motor. The other stayed nearer the bow, checking boxes and lines. The younger man sat near the middle, resting, smoking, letting the experienced hands do what experience does—move without wasting words.

At that hour conversation comes in short phrases. “Ease off.” “Watch the line.” “Cut left.” You don’t chatter before sunrise on a working boat. You listen. You watch. You conserve energy like money.

Then the sound changed first.

Not loud. Just noticeable.

The water around them seemed thicker, as if something had changed the density beneath the hull. The boat nudged sideways—only a little, but enough that the man at the motor frowned because there was no wind and no wake from another vessel. The fog in that spot wasn’t heavy, yet small ripples appeared along the side of the boat: circles and tight rings, the kind you get when something large moves just below the surface.

That wasn’t unusual. Large fish did it. Logs did it when currents bumped them. Alligators could do it too.

What made the crew look at each other was the way the ripples didn’t move in a line. They seemed to circle the boat, closing into a loose semicircle, as if something was traveling around them rather than past them.

At about 4:30 a.m., when they were roughly a mile and a half from the nearest dry shore—close enough to see reeds and cypress, far enough that swimming would be a terrible idea—there was a short, sharp thud at the stern.

Not hard enough to capsize them.

Hard enough to make all three men not holding the net turn their heads at the same time.

The cousin at the motor thought, instantly, of a sunken pole or log. Those things happen. They can crack a hull. You hit one, you check the damage, you curse, you keep going. The bayou is full of half-hidden dangers that are still normal dangers.

Raymond was standing sideways to the water holding the net, ready to throw.

What happened next took seconds.

The young man, sitting near the middle, swore later that he saw the water behind the stern rise—not in a splash, not in a wake, but in a small mound, as if something large had pushed up from below and lifted the surface like a blanket.

And then Raymond moved in a way no one could explain.

He swayed backward—not like a man who slipped on wet boards, not like a man who lost his balance. It was as if something had pulled him.

His feet left the deck.

His body went overboard almost without sound.

He didn’t shout. He didn’t flail. There was no dramatic splash, no thrashing panic. One moment he was there, and the next he was gone over the side, swallowed by brown water that didn’t even seem to want to admit it had taken him.

One cousin—standing nearest the stern—claimed that when Raymond was already in the water, he saw a dark mass under the surface right where Raymond had vanished. The mass was large, more than three meters long by his estimate, resembling the back of a huge animal.

But it didn’t move like an alligator.

There was no smooth glide, no lazy tail sweep.

It moved with a short, powerful jerk, like something snapping downward with purpose—as if it had hooked a weight and was hauling it into deeper shadow.

The younger man said he saw something else—something worse.

He said the dark mass rose slightly above the surface, and for no more than a second he saw what looked like a head. Not an alligator’s head. It was short and broad, without a long snout. On the sides were small protrusions—thickenings that made him think of rudimentary horns or growths.

He emphasized, over and over, that he saw it only for an instant. One flash. One impossible outline. And then it went under again, taking whatever it had with it.

The third man, closer to the bow, said he saw only a larger-than-alligator silhouette—a brown shape that moved with intention. His view was worse. The angle was wrong. The fog and distance stole detail.

But all three agreed on one point, even years later: it was not a tree. It was not a normal alligator. Whatever moved under the stern was alive, large enough to shift the boat, and strong enough to drag a grown man away as if he weighed nothing at all.

For a moment their minds refused to work properly. Shock can make a simple task impossible. The boat stopped. The motor went quiet. All three men rushed to the side where Raymond had been.

The water churned for a few seconds.

Then it calmed again, as if the bayou had drawn a curtain.

No head surfaced. No hands. No bubbles. No cry.

They called his name, their voices turning sharp and ragged. They threw what they could into the water—ropes, a buoy, anything that might catch him if he came up confused. They leaned so far over the gunwale they risked tipping the boat, desperate to see any sign of him in water that was too opaque to show even the truth of a drowned man.

Nothing appeared.

After minutes that felt like hours, they understood what every waterman knows but hopes never to face: there are moments when the bayou offers no second chances. There was little they could do alone. Not out there. Not with that visibility. Not with that depth and those reeds and that endless system of branching canals.

One cousin started the motor and they headed back to the nearest pier to call for help, trying to memorize the route in case they had to lead searchers back. In Bayou Bianu it’s easy to lose your bearings. The coastline repeats itself. Landmarks vanish behind mist and reeds. Every turn looks like the last.

By midmorning the sheriff’s department and the Coast Guard had been notified. Search boats went out. Volunteers joined in. For three days they checked shorelines, flooded pockets, reed edges, and canal branches, looking for the most basic thing a family needs: a body.

The measurements mattered, and the men knew it. The canal at that point did not exceed eight feet. That is shallow water. In shallow water, bodies usually don’t disappear completely. Even when a man isn’t wearing a life jacket, his body tends to be found near the bottom. If not immediately, then later—when gases bring him up and the current carries him somewhere that can be reached.

Raymond Boso’s body was never found.

Not in the canal. Not in adjacent branches. Not farther down the system. Not washed up in reeds. Not caught on a snag. Not floating into the open.

Only two things surfaced: his life jacket and one shoe.

The life jacket came up about a day after the accident, roughly five hundred yards downstream from where they believed he went under. That distance wasn’t far; the current in that bayou is weak. But what startled the investigators—and deeply unsettled the men who had been on the boat—was the damage.

The straps that secured the jacket to Raymond’s body were torn.

Not cut. Not neatly slashed. Not gnawed through in a way that would leave tooth impressions. Torn—fibers stretched and shredded like rope pulled until it failed. The material didn’t show the characteristic alligator tooth marks that locals knew well. There were no punctures, no patterned tears, nothing you could easily point to and say, Yes, a gator did this.

The official conclusion that went to the family and insurance company was standard: an accident caused by falling overboard. The documents suggested Raymond might have hit his head, lost consciousness, and drowned. Alligators were carefully not mentioned. A line noted that the body was not recovered and could have been lost in the complex canal system.

It was a tidy explanation for an untidy reality.

Unofficially—quietly, in conversations that never became ink on paper—one officer involved in the search admitted to an acquaintance that several details bothered him. First, the depth. An adult rarely vanishes completely in eight feet of water. Second, the life jacket. Torn straps without teeth marks didn’t match typical alligator behavior. In a real attack, a gator grabs, rolls, drowns; it leaves a signature of damage on fabric and flesh.

In an informal memo that never made it into the official case file, an employee noted that witness descriptions aligned with something else: local legends about a creature living in the Bianu canals.

Those stories had been circulating for decades. Locals used different names—Bayou Devil, Big Head, and older French dialect terms handed down through Cajun families. The descriptions varied, but the theme stayed stubbornly consistent: something larger than an alligator, with a broad head and short neck, capable of coming up under boats and taking what it wanted.

No official report recorded legends. Reports were for facts. Legends were for bars, for marinas, for men speaking low after too much coffee at dawn.

But after Raymond vanished, facts began to behave like legends.

That section of canal was formally closed to private fishing soon after—“for environmental reasons.” There was talk of pollution, restoration of vegetation, new restrictions. On paper it looked like regulation. In reality, people understood it wasn’t only about the environment. Too many questions clung to that bend in the canal like fog that wouldn’t burn off.

Over time, the place gained a nickname used more often than its map name: Devil’s Cut.

That is what people called it in bars, in boat yards, in conversations among themselves. Younger fishermen avoided it. Older fishermen added stories like nails in a board: splashes at night where there should be no boats, lights moving on the water where no road was close enough to throw headlights, boats that felt pulled sideways despite calm current.

There were rational versions, of course. A gator struck the boat. Raymond lost his balance, hit his head, drowned. A floating log rolled under the hull and shifted the boat at the wrong moment. A medical episode—stroke, fainting—sent him into the water. All of it was possible.

But none of those explanations accounted for everything together: the ripples circling the boat, the mound of rising water, the sensation of a purposeful downward jerk, the brief glimpse of a broad head with protrusions, the torn straps without teeth marks, and—most of all—the absence of a body in shallow water.

There is one more detail that rarely makes it into retellings, but it comes up in private conversations like a confession.

Years later, one of Raymond’s cousins—no man prone to fantasy—admitted he sometimes woke at night feeling the boat tilt again beneath him. Not a dream, not fully. More like muscle memory. He said that in the instant Raymond disappeared, he felt something that has haunted him ever since: not that they had been bumped by an animal or a log, but that Raymond had been taken.

Not in a mystical sense. Not by the devil. Taken as prey.

As if something underwater had watched boats in that area for a long time, learned their rhythm, knew where a man would stand with a net in his hands, and waited for a moment when a single hard tug would be enough.

Officially, the case is closed. No new evidence has emerged. The canal has grown more overgrown in places. Part of it remains off limits. On maps it is still Bayou Bianu. But for those who know the story, the name on the map no longer fits the place.

Because in water less than three meters deep, a grown man vanished so completely that he was not found after three days, or three weeks, or years.

And every time another boat passes that bend, someone on board looks at the water a little longer than usual.

Not because they believe in monsters.

Because they believe in what they saw: the surface rising, the stern shifting, the sudden absence of a man who should have splashed and surfaced and cursed and climbed back in.

Because if even part of the three survivors’ account is true, then it isn’t only fish and alligators living in those murky canals.

And whatever took Raymond Boso—whatever it was—has never been clearly seen again.

News

The Coca-Cola at the Edge of Death

They arrived without a word, without an explanation, and without the smallest hint of what awaited them. The silence was so thick it felt unnatural, pressing against…

THE NIGHT THE ENEMY GAVE HIS COAT

December 15, 1944 – Bavaria, Germany The cold arrived like a weapon. At just twelve degrees Fahrenheit, the air outside Munich cut through flesh and bone with…

Inside One of the Most Compelling Bigfoot Evidence Trails Ever Documented

In the ongoing debate over the existence of Bigfoot, few forms of evidence have generated as much fascination—and controversy—as footprints. Blurry photographs and fleeting sightings can be…

Footprints in the Dark: When the Wilderness Fought Back

For centuries, legends have warned that the wilderness is not empty. That beyond the reach of roads, cell towers, and human certainty, something else still moves. Something…

Whispers in the Wilderness: The Search for Bigfoot

Across America and beyond, tales of an elusive man-like creature known as Bigfoot or Sasquatch have captivated the imagination of many. Thousands of reports, photos, and videos…

End of content

No more pages to load