In July 1996, two fishermen on the Pea River hauled up something that didn’t belong in any tackle box, any livewell, any ordinary river story. It came out of the water in a slow, resistant rise, as if the river itself didn’t want to surrender it. At first glance it looked like a pale knot of driftwood and line. Then the sun caught it—clean, chalky white—and both men went silent.

It was a human skeleton.

Not scattered the way remains often are in moving water, not darkened by silt and stained by months of river decay. Almost complete. Almost polished. And etched across the ribs and collarbone were dozens of thin, shallow cuts—parallel in places, clustered like the marks of something that worked quickly and repeatedly, as if cleaning meat from bone were a method, not a coincidence.

The bones belonged to a man who had vanished exactly one year earlier.

And once the coroner began writing his notes, the Pea River stopped being merely a sleepy Alabama tributary in the public imagination. It became a question with teeth: what kind of thing can make a grown man disappear from a boat without a struggle—then return him as spotless bones with damage no one could name?

To understand why the case still lingers in whispers along Houston County backroads, you have to go back to the morning of July 14, 1995, a Friday already hot enough to make the air feel thick.

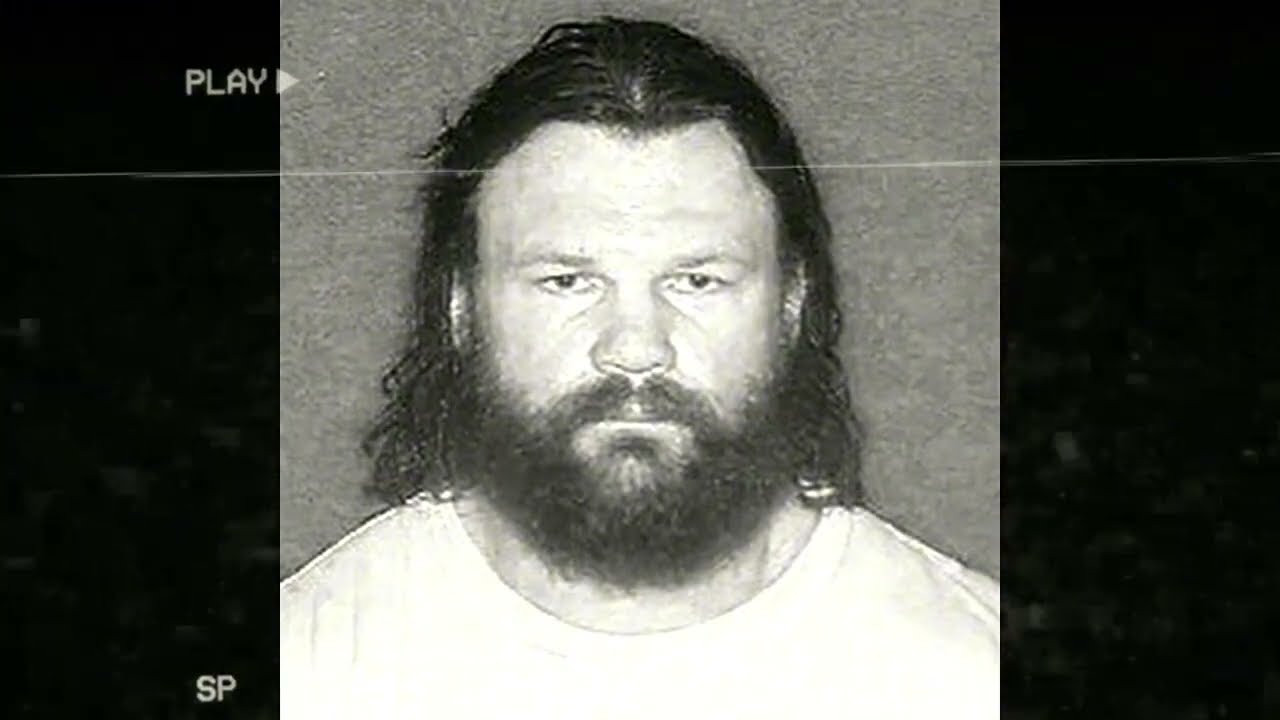

Kenneth Lawrence was forty-two, a welder from Dothan, Alabama, and a man made of habits. The welding shop was loud, bright, and relentless; the river was his opposite. On free weekends he took his small aluminum boat to the Pea River the way other men went to church—faithful, predictable, and quietly protective of the routine. He wasn’t reckless. He respected the water and knew its dangers the way locals always do: alligators, cottonmouths, sudden weather, hidden snags. The Pea River was a slow tributary feeding the larger Choctawhatchee system, its bends familiar enough that Kenneth could picture them with his eyes closed.

That morning he ate breakfast like always, kissed his wife Sharon, and promised he’d be back by sunset. A friend helped him launch from a small unofficial dock—more a worn patch of bank than a formal ramp. Later, that friend told the sheriff’s office that Kenneth seemed in a great mood, the kind of calm contentment that comes from knowing exactly where you’re headed and what you plan to do once you get there.

Kenneth waved and called back the last words anyone close to him would ever hear:

“I’m going to drift downstream to the old bridge and try for catfish.”

The old bridge was about five miles downriver—an easy run, a few hours there and back, nothing unusual. It wasn’t a trip into the wilderness. It was a man following a familiar thread through a familiar landscape.

When Kenneth didn’t return by nightfall, Sharon tried to be patient. In 1995, cell phones weren’t common in rural Alabama, and even if Kenneth had one, the river had plenty of dead zones where bars meant nothing. Still, Kenneth was punctual. He didn’t disappear casually, not the way some men do when they’ve decided they’d rather not be found.

An hour passed. Then another.

By midnight Sharon’s patience turned to certainty, the kind that arrives without drama but with a hard, cold edge. She called the Houston County Sheriff’s Office. The deputy on duty spoke gently, offering the usual comfort people offer when they want to keep fear from spreading: maybe the engine stalled, maybe Kenneth decided to camp by the river, fishermen do that sometimes.

Sharon listened, but she did not accept it. She knew her husband’s habits, and this wasn’t one of them.

At dawn the next day, the search began.

Friends, volunteers, and sheriff’s boats moved along Kenneth’s presumed route from the launch site toward the old bridge, scanning the murky surface for anything out of place. The weather was perfect—clear, windless. The river ran calm with a weak current, almost imperceptible. The Pea River’s water was muddy, brown, and opaque from the bottom silt, but the surface visibility was decent enough that an overturned boat or floating body should have been spotted.

The first day yielded nothing.

No boat. No oars. No hat. No cooler. No trace on the shore. Not even a scrap of fabric or a broken branch to suggest a frantic climb out of the water.

On Sunday, July 16, the second day, one patrol boat rounded into a reed-covered backwater about two miles from Kenneth’s starting point. There, drifting near the shoreline as if waiting patiently to be claimed, was Kenneth’s aluminum boat.

It was upright.

Not sunk. Not overturned. Not wrapped around a log.

Just rocking gently, empty.

Deputies approached expecting the usual unpleasant math of accidents: a tipped boat, a snagged line, blood, scratch marks, a trail of struggle in the mud. But the scene refused to cooperate. The motor had been lifted out of the water. Inside the boat lay an overturned plastic bucket with fishing tackle spilled out, the mess suggesting a sudden movement—something quick enough to knock a bucket but not violent enough to smash the hull. Kenneth’s hunting knife was still there, safely sheathed. His favorite fishing rod was there too.

And it was snapped in half.

Not cracked. Not bent. Snapped cleanly as if something on the other end of the line had pulled with tremendous sudden force—enough to break a sturdy fiberglass catfish rod designed to handle large fish.

Deputies checked the boat and the bank like men looking for a missing sentence in a written page. No blood. No teeth marks. No gouges along the side that might suggest a collision with an alligator. The mud on the shore was untouched—no boot prints, no slide marks, nothing indicating Kenneth had climbed out or been dragged.

It looked, in the most unnerving way, as if Kenneth Lawrence had simply stood up and vanished from his own boat.

The broken rod was the only clue with a voice. It spoke of power—of a force that could yank hard enough to snap fiberglass yet somehow leave the boat un-capsized and the shoreline unmarked. If Kenneth had hooked something massive, you’d expect chaos: a spinning boat, a tangle of line, maybe a panicked lunge. But the evidence offered no drama—only absence.

Divers were brought in. They surveyed the riverbed in the area where the boat was found. The bottom was described as flat and muddy, with no deep holes, no strong underwater currents where a body might be pinned. The river there was shallow—ten to twelve feet at most. Search teams with dogs combed through miles of dense cypress thicket and swampy banks, pushing into places where humidity and insects made every minute feel longer.

A week passed.

Kenneth Lawrence did not return, did not surface, did not wash up downstream the way bodies often do. He left no trail on land, no clear sign in the water, and no explanation in the boat he had abandoned without meaning to.

The active search was called off.

The official version—reluctantly accepted by police and family because it was the only version that came with paperwork—was an accident. Kenneth must have stood up, lost his balance, fallen, hit his head, drowned. Perhaps alligators took him. Perhaps the river carried him away.

It was simple. It was familiar. It was the kind of story that lets a community keep functioning.

But it did not explain the rod.

And it did not explain the complete absence of any struggle.

For a year, the Pea River held its secret.

Then, in mid-July 1996, on a day so hot the air itself seemed to sweat, two locals—Mark Riley and his son David—were fishing about three miles downstream from where Kenneth’s empty boat had been found. They drifted slowly, letting the river do the work. David’s line tightened hard, sudden and heavy, like it had caught a submerged log.

Mark helped him pull.

Whatever they had hooked resisted awkwardly—not with the smooth fight of a fish, not with the stationary stubbornness of a snag. It felt like weight shifting in reluctant increments.

When their catch broke the surface, David cried out.

In the murky brown water, tangled in fishing line, was a pale cluster that resolved into human anatomy: ribs, a spine, the curve of a skull. A human skeleton—surprisingly white, almost clean—came up dripping like something the river had rinsed and polished for display.

It was Kenneth Lawrence.

Deputies arrived to find Mark and David sitting in their boat in complete silence, staring at the tarp where the remains lay. River men see hard things. They see drowned animals, dead fish, occasionally worse. But this was different—because it wasn’t merely death. It was the manner of it. The condition.

The skeleton was transferred to the county coroner’s office.

Dr. Alan Peek had thirty years of experience and the steady demeanor of someone who had seen tragedy in every shape it takes. He began his examination expecting the typical patterns: darkened bones, silt staining, scavenger marks, missing smaller bones, signs of the river’s messy appetite.

What he found instead made him frown, then pause, then go back over the remains like he didn’t trust his own eyes.

First: the cleanliness. There were virtually no traces of soft tissue. That alone wasn’t extraordinary after a year, but the way the bones were clean was wrong. River scavengers—crayfish, catfish, turtles—leave evidence. They scratch. They chip. They gnaw in a way that makes bone look worked-over and battered, not smooth and bright. Bone left in water tends to darken, to carry the river’s signature like a stain.

Kenneth’s bones looked almost boiled.

Then Dr. Peek focused on the rib cage and shoulder girdle. Under magnification, he found dozens of thin, shallow cuts across ribs, clavicles, shoulder blades—marks so numerous they formed clusters. They did not resemble knife marks. Too many. Too chaotic and yet grouped. The depth and shape varied slightly, as though made by a series of uneven teeth—small, sharp, frequent.

He ruled out alligators immediately. Alligator jaws crush. They leave punctures, fractures, breaks. These were slicing marks, not crushing marks.

He considered boat propellers—another common culprit in water-related trauma. But the cuts appeared at different angles and across bones that a propeller could not physically reach in a typical encounter. Propellers also leave deeper, more regular strikes, a pattern that repeats with mechanical precision. These marks were not regular. They were intimate, repetitive, and oddly purposeful.

Unable to land on a rational explanation, Dr. Peek sent select bones—those with the most obvious damage—to Auburn University’s Department of Zoology and Forensic Anthropology.

The response arrived weeks later, and instead of solving the case, it made the mystery harder to hold.

The conclusion was blunt: the damage did not correspond to the teeth or claws of any known predator or scavenger inhabiting the Choctawhatchee river system. Alligators, large catfish, gar, turtles—none fit. The morphology was wrong.

Then the experts added a detail that chilled the investigators who read it: many cuts had a clear direction—from bottom to top and toward the center of the chest—suggesting the body had been gripped and pulled inward, flesh removed by small frequent movements.

It read less like nature feeding and more like a method.

A second finding arrived like a shadow crossing the room.

Forensic scientists took samples from microscopic cracks in vertebrae and marrow channels. Under the microscope they found particles of silt and plant pollen not typical of the Pea River’s main channel: swamp cypress, waterlily, and diatom algae associated with stagnant, oxygen-poor “black pools” and bogs—waters abundant away from the river flow in isolated backwaters.

It meant Kenneth Lawrence’s body had not remained in the river where it was found. At least for a time, it had been elsewhere—in a stagnant, anaerobic environment like deep silt or a peat bog.

Then it had been moved.

How does a body move from a black, isolated pool back into the river, three miles downstream, as an almost complete skeleton—cleaned in a way biology couldn’t easily explain?

The official report that followed was brief and vague, as if written by someone eager to close the file before the file began asking questions.

Cause of death: drowning. Damage to bones: postmortem, caused by unidentified river fauna.

The family received a death certificate. A funeral happened. The county returned to its routines.

But in the sheriff’s unofficial archive, in the folder labeled LAWRENCE, there was an extra note—stapled, not filed neatly with the rest. Dr. Peek’s handwriting. Only a few sentences, but they carried more weight than the entire report.

The condition of the bones indicates prolonged stay in an anaerobic environment, possibly deep silt or peat bog. The cleaning of the bones shows signs of mechanical rather than biological impact. The body was moved from its original resting place.

The word mechanical was underlined twice.

It was around that time that an older deputy—raised in the area, familiar with the way local stories cling to certain stretches of water—mentioned something he hadn’t said out loud in years.

Old folks near the swamps, he said, sometimes talked about a creature they called the Crawling Thing.

Not a ghost. Not a spirit. In those stories it was a living animal that lived in the deepest, dirtiest swamps. Descriptions varied, as they always do when fear travels by word of mouth, but the core remained: something about the size of a human, moving on all fours, skin smooth and slick, pale and shining like fish skin. And a mouth full of small needle-like teeth—more like a fish’s than a mammal’s.

According to legend it hunted at night, dragging prey into stagnant water and leaving only clean bones.

Until Kenneth Lawrence, the Crawling Thing was a story to scare children away from black water after sunset.

After Kenneth Lawrence, it was a story men repeated more carefully—because polished bones with strange cuts are hard to laugh off.

Rumors might have stayed rumors if not for a leak.

Details of Auburn’s analysis—enough to suggest “unidentified” and “not matching known fauna”—made their way to a local newspaper through an anonymous source. Once it was printed, even lightly, the community’s imagination did what it always does: it filled in blanks. The Crawling Thing stopped being folklore and began to feel like an explanation waiting just beneath the surface.

A local journalist named Steven Gaines, working for a small radio station in Dothan, decided to dig. For months he interviewed older residents living in isolated houses near swamps and backwaters. At first people resisted. In the South, you learn early that speaking too openly about strange things invites ridicule, and ridicule is a kind of social punishment.

But Kenneth’s story had cracked something open.

An elderly hunter in his seventies told Gaines that his father and grandfather had always forbidden him from going near the black backwaters after sunset. Something lived there, they said, that “cleans its trails.”

When Gaines asked what that meant, the old man stared at him with a flat look and explained: if a deer wandered into the backwaters to drink and got stuck in mud, there would be no trace after a few days. No bones. No hide. Just a clean spot, as if the animal had never existed.

Another resident—a woman with hands tough from decades of work—told a story from the late 1980s. Her dog, a large Rottweiler, broke free one night and ran toward the swamp barking furiously. It never returned. In the morning she found only the collar at the edge of her property, lying in mud.

The collar wasn’t torn.

It was neatly opened, as if unclasped.

That detail—small, domestic, wrong—stuck to Gaines’s ribs when he drove home. Predators tear. They don’t unfasten.

The most disturbing account he uncovered involved two teenagers—brothers named Caleb and Joshua Wilks—who had gone night fishing along a tributary of the Pea River not far from the black pools locals avoided.

At around 2:00 a.m., they heard a sound from the backwater.

Not a splash.

A wet slapping sound, heavy and rhythmic, like something large and soaked pulling itself up onto mud.

Curiosity overcame fear, the way it often does in boys who haven’t learned which questions can get you killed. They lowered their flashlights and crept closer.

In dim moonlight, about thirty meters away, they saw something moving along the muddy shore.

It was roughly the size of a small adult human, but it moved on all fours. Its motion was awkward and jerky—wrong in a way that made their minds refuse to label it—but it was fast when it chose to be. Its skin looked pale and slick, glistening like an amphibian’s hide. The creature stopped and raised what could be called a head. The boys couldn’t make out eyes, but they saw a wide dark mouth opening and closing, making a quiet sucking sound—like breathing underwater.

Then a branch cracked beneath one boy’s foot.

The creature froze.

In the next instant it slid back into the black water with astonishing speed and almost no sound, as if the pool had opened and swallowed it. The boys ran without speaking, leaving rods and tackle behind. They told their father—who, in this version of events, had law enforcement connections—and the story didn’t get filed, but it did get heard.

A few days later, according to local accounts, a group of men arrived in unmarked pickup trucks. They introduced themselves as employees of the Alabama Commission on Fisheries and Wildlife. They cordoned off several square miles of swamp and backwaters, including the tributary where the boys claimed they’d seen the creature.

The official reason was bureaucratic and safe: assessing rare amphibian populations and investigating potential water pollution.

They stayed about two weeks taking samples of water and silt. No one in town ever learned the results. But after they left, signs remained at swamp entrances—DANGEROUS AREA. NO ENTRY.

From that point on, the Pea River didn’t change physically.

It changed in people’s minds.

Fishermen started avoiding the black backwaters, preferring open water upstream where you could at least see what might be coming. Hunters who used to cut through certain swamp edges began taking longer routes without admitting why. Parents told children to stay away from the still pools, and their voices carried a new seriousness—less folklore, more rule.

No new official victims have been tied to those waters. No new missing-person cases have made headlines the way Kenneth Lawrence’s did.

And yet, the fear remains, because fear doesn’t require new evidence to survive. It only requires a story that fits the shape of what people already feel.

Locals say that on particularly quiet, windless evenings, if you stare long enough at the smooth surface of the black pools, you might see a short fast ripple traveling against the current—as if something very large and flat is passing just below the surface without breaking it.

And if you listen carefully, you might hear the sound the Wilks brothers described.

A quiet, almost silent breath coming from under the water.

The Pea River still carries catfish and gar and logs and silt the way it always has. It still looks, in daylight, like any other Southern river: slow, muddy, unconcerned. But for those who know the case—who remember the empty boat, the snapped rod, the white bones with their thin mechanical cuts—there is an extra layer to the water now.

A sense that the river doesn’t merely hold secrets.

Sometimes, it returns them—cleaned, arranged, and marked—like a warning left on the doorstep.

And the most disturbing part is not what the authorities wrote on paper.

It’s what they underlined twice in private.

Mechanical.

As if something down there is not only hungry—but precise.

News

The Coca-Cola at the Edge of Death

They arrived without a word, without an explanation, and without the smallest hint of what awaited them. The silence was so thick it felt unnatural, pressing against…

THE NIGHT THE ENEMY GAVE HIS COAT

December 15, 1944 – Bavaria, Germany The cold arrived like a weapon. At just twelve degrees Fahrenheit, the air outside Munich cut through flesh and bone with…

Inside One of the Most Compelling Bigfoot Evidence Trails Ever Documented

In the ongoing debate over the existence of Bigfoot, few forms of evidence have generated as much fascination—and controversy—as footprints. Blurry photographs and fleeting sightings can be…

Footprints in the Dark: When the Wilderness Fought Back

For centuries, legends have warned that the wilderness is not empty. That beyond the reach of roads, cell towers, and human certainty, something else still moves. Something…

Whispers in the Wilderness: The Search for Bigfoot

Across America and beyond, tales of an elusive man-like creature known as Bigfoot or Sasquatch have captivated the imagination of many. Thousands of reports, photos, and videos…

End of content

No more pages to load