Well-preserved baby mummy (of approximately 200 corpses with European features that were excavated in the Tarmi basin).

refully prepared for the afterlife, tells a poignant story of life, death, and the beliefs of a long-lost civilization.

The infant’s eyes were covered with dark blue stones, and red threads had been inserted into his nasal passages—ritualistic details that hint at the spiritual significance of his burial. Alongside him were items of profound meaning: a piece of cow leather and a small copper feeding bottle, known as a biberón. These objects, though simple, carried a weight of symbolism, offering a glimpse into the worldview of the people who laid him to rest.

The Encrusted Pottery Culture and the Afterlife

This burial site was part of a broader cultural tradition tied to the encrusted pottery culture of Central Europe, which flourished between 2000 and 1500 BC. These people, known for their intricate ceramics, believed deeply in the concept of an afterlife. Their funerary practices reflected a careful preparation for the journey to the other world, a place they envisioned as both mysterious and perilous.

.

.

.

One of the most striking aspects of their burial customs was the inclusion of age-appropriate funerary items. Adults were buried with large ceramic vessels, children with smaller ones, and infants with tiny pots or bottles, such as the one found with the baby in Qizilchoqa. These vessels, often decorated and carefully crafted, were not just offerings—they were tools for survival in the afterlife. The people of this culture believed that the other world was “a thirsty place,” and ensuring that the deceased had enough to drink was a sacred responsibility.

The Thirsty Place: A Universal Belief?

The idea of the afterlife as a thirsty place is not unique to the encrusted pottery culture. Across civilizations, water has held profound symbolic significance in death rituals. In ancient Egypt, for example, the Nile River was central to both life and the afterlife, and offerings of water or wine were common in tombs. Similarly, in Mesopotamia, the dead were often buried with vessels of water to quench their thirst in the underworld.

But where and when did this belief originate? Was it born from the harsh realities of life in arid regions, where water was scarce and survival depended on its availability? Or was it a metaphorical reflection of the soul’s journey, a way of expressing the challenges of crossing into the unknown?

The burial practices of the encrusted pottery culture suggest a deep connection between the living and the dead, one that transcended the boundaries of life. By providing the deceased with water, they ensured not only their survival in the afterlife but also maintained a bond of care and responsibility. This practice was not just a ritual—it was a testament to the enduring love and respect for those who had passed.

The Baby of Qizilchoqa: A Story of Love and Loss

The baby mummy discovered in Qizilchoqa is a poignant reminder of this connection. His burial, though simple, was imbued with care and meaning. The dark blue stones covering his eyes may have symbolized protection or guidance for his journey. The red thread in his nasal passages could have been a ritualistic gesture, perhaps to ward off evil or to connect him to the spiritual realm. The piece of cow leather and the small copper feeding bottle were likely chosen with the same intent—to provide comfort and sustenance in the afterlife.

The discovery of this infant mummy also sheds light on the broader cultural exchanges along the Silk Road. The Tarim Basin, located at the crossroads of Central Asia and northern China, was a melting pot of ideas, goods, and traditions. The presence of European-style burial practices in this region speaks to the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations and the shared human desire to honor and care for the dead.

A Legacy of Belief

The concept of the afterlife as a thirsty place continues to resonate in some cultures today. In Central Europe, for example, it is still considered important to ensure that the deceased are provided with water for their journey. This enduring belief reflects the universal human need to make sense of death and to care for loved ones, even after they have passed.

The baby of Qizilchoqa, though silent, speaks volumes about the people who buried him. His tiny body, preserved by the dry desert sands, is a testament to the love and hope that transcended the boundaries of life and death. Through him, we catch a glimpse of a world where the living and the dead were connected by rituals, symbols, and the enduring belief in an afterlife.

As we uncover more about the encrusted pottery culture and their burial practices, we are reminded that the past is not so distant. The rituals and beliefs of ancient civilizations continue to echo in our own lives, shaping the ways we remember and honor those who came before us. The baby mummy of Qizilchoqa is more than an archaeological discovery—it is a bridge to the humanity of our ancestors and a reminder of the timeless connections that bind us all.

News

Thrown from the Bridge, Saved by a Stranger: The Golden Puppy Who Changed Everything

Thrown from the Bridge, Saved by a Stranger: The Golden Puppy Who Changed Everything He was barely a month old—a tiny golden retriever puppy, cream-colored fur still…

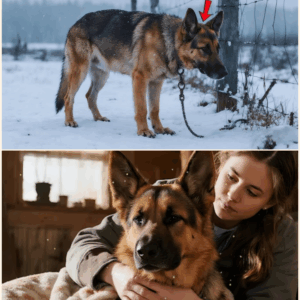

Chained in the Snow: The Emaciated German Shepherd Who Saved a Town—A Tale of Redemption, Courage, and Unbreakable Bonds

Chained in the Snow: The Emaciated German Shepherd Who Saved a Town—A Tale of Redemption, Courage, and Unbreakable Bonds The amber eyes stared up from the snow,…

Dying Dog Hugs Owner in Heartbreaking Farewell, Then Vet Notices Something Strange & Halts Euthanasia at the Last Second!

Dying Dog Hugs Owner in Heartbreaking Farewell, Then Vet Notices Something Strange & Halts Euthanasia at the Last Second! It was supposed to be the end. The…

Everyone Betrayed Him! A Frozen K9 German Shepherd Sat in the Storm—He No Longer Wanted to Survive, Until One Man’s Plea Changed Everything

Everyone Betrayed Him! A Frozen K9 German Shepherd Sat in the Storm—He No Longer Wanted to Survive, Until One Man’s Plea Changed Everything The storm had not…

Girl Had 3 Minutes to Live — Her Dog’s Final Act Made Doctors Question Everything They Knew

Girl Had 3 Minutes to Live — Her Dog’s Final Act Made Doctors Question Everything They Knew A heart monitor screamed into the stillness of the pediatric…

Unbreakable Bond: The Heartwarming Journey of Lily and Bruno, A Girl and Her Dog Healing Together

Unbreakable Bond: The Heartwarming Journey of Lily and Bruno, A Girl and Her Dog Healing Together The shelter was quiet that morning, the kind of quiet that…

End of content

No more pages to load