“Unveiled: How a Single Dinosaur Skull Could Rewrite Paleontology’s History”

In a groundbreaking discovery, paleontologists from the University of Alberta have unearthed a remarkably well-preserved Styracosaurus skull in the badlands northwest of Dinosaur Provincial Park. Discovered in 2015 by then-graduate student Scott Persons, this fossil is challenging long-held assumptions in the field of paleontology and could redefine how scientists identify dinosaur species.

The Styracosaurus, a horned dinosaur over 5 meters in length, is known for its distinctive fan of long horns. However, what makes this particular skull—affectionately nicknamed “Hannah” after Persons’ dog—extraordinary is the striking asymmetry between its left and right sides. Traditionally, when one side of a dinosaur skull is missing, paleontologists have assumed symmetry with the preserved side. Hannah’s skull shatters this notion. “The differences in the skull’s left and right sides are so extreme that, had we found only isolated halves, we might have concluded they belonged to two different species,” explained Professor Scott Persons, now a curator at the College of Charleston.

.

.

.

This facial imperfection suggests a significant morphological variability within the Styracosaurus genus, akin to the varying antler patterns seen in modern deer and moose. Professor Holmes, part of the research team, noted, “Hannah shows dramatically that dinosaurs could be the same way. Like antlers, the pattern of dinosaur horns could vary significantly.” This revelation means that many fossils previously thought to represent unique species may need re-evaluation, potentially reshaping our understanding of dinosaur diversity.

The discovery’s implications extend beyond mere classification. It highlights the importance of questioning assumptions in science. “The skull shows how much variability there was in the genus,” Holmes added. Fossils once deemed distinct might simply reflect individual differences rather than separate species, urging paleontologists to revisit existing collections with fresh eyes.

Adding to the excitement, the team collaborated with the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Alberta to create a detailed 3D model of Hannah’s skull. Professor Persons shared, “Ahmed Qureshi and graduate student Baltej Rupal assisted us in performing a 3D laser scan. This allowed our publication to include a digital reconstruction, enabling scientists worldwide to download and inspect the model in detail.” This digital approach represents the future of paleontological research, making “digital dinosaurs” accessible for global study and collaboration.

The personal touch behind Hannah’s name adds a heartwarming note to the discovery. “Hannah the dinosaur is named after my dog,” Persons revealed. “She’s a good dog, and I knew she was home missing me while I was away on the expedition.” Though the dinosaur’s gender remains unknown, the nickname reflects the deep connection researchers often feel with their finds.

This single skull, with its unexpected asymmetry and the technological advancements it showcases, threatens to turn paleontology on its head. As scientists re-evaluate past assumptions, Hannah stands as a testament to the ever-evolving nature of discovery, reminding us that even ancient bones can hold revolutionary secrets.

News

Thrown from the Bridge, Saved by a Stranger: The Golden Puppy Who Changed Everything

Thrown from the Bridge, Saved by a Stranger: The Golden Puppy Who Changed Everything He was barely a month old—a tiny golden retriever puppy, cream-colored fur still…

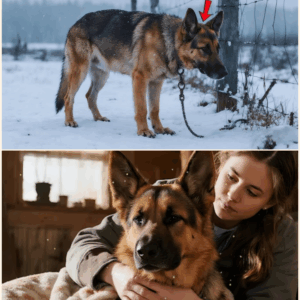

Chained in the Snow: The Emaciated German Shepherd Who Saved a Town—A Tale of Redemption, Courage, and Unbreakable Bonds

Chained in the Snow: The Emaciated German Shepherd Who Saved a Town—A Tale of Redemption, Courage, and Unbreakable Bonds The amber eyes stared up from the snow,…

Dying Dog Hugs Owner in Heartbreaking Farewell, Then Vet Notices Something Strange & Halts Euthanasia at the Last Second!

Dying Dog Hugs Owner in Heartbreaking Farewell, Then Vet Notices Something Strange & Halts Euthanasia at the Last Second! It was supposed to be the end. The…

Everyone Betrayed Him! A Frozen K9 German Shepherd Sat in the Storm—He No Longer Wanted to Survive, Until One Man’s Plea Changed Everything

Everyone Betrayed Him! A Frozen K9 German Shepherd Sat in the Storm—He No Longer Wanted to Survive, Until One Man’s Plea Changed Everything The storm had not…

Girl Had 3 Minutes to Live — Her Dog’s Final Act Made Doctors Question Everything They Knew

Girl Had 3 Minutes to Live — Her Dog’s Final Act Made Doctors Question Everything They Knew A heart monitor screamed into the stillness of the pediatric…

Unbreakable Bond: The Heartwarming Journey of Lily and Bruno, A Girl and Her Dog Healing Together

Unbreakable Bond: The Heartwarming Journey of Lily and Bruno, A Girl and Her Dog Healing Together The shelter was quiet that morning, the kind of quiet that…

End of content

No more pages to load