Secrets of the Nebra Sky Disk: Ancient Stargazers’ Code Unveiled

Beneath the rolling hills of Mittelberg, Germany, a secret slept for millennia—one that would rewrite everything we thought we knew about Europe’s ancient peoples. In 1999, fortune and fate collided when two treasure hunters, digging illegally under cover of darkness, unearthed a small, corroded bronze disk. At first glance, it seemed unremarkable. But as the soil fell away, golden symbols shimmered from its surface: a crescent moon, a radiant sun, and a scattering of stars—among them, a tiny cluster that mirrored the Pleiades.

This was the Nebra Celestial Disk, and it would soon be hailed as the world’s oldest known map of the night sky.

A Puzzle from the Distant Past

Dating back at least 3,600 years, the Nebra Sky Disk stunned archaeologists. How could such advanced astronomical knowledge exist in Bronze Age Europe—a land presumed to be the realm of warriors, not stargazers? The disk’s creators had mapped the heavens with uncanny precision. The two golden arcs on the sides marked the sun’s setting and rising points at the solstices, perfectly matching the latitude of Mittelberg. A smaller arc at the bottom, shaped like a boat, echoed ancient myths of the sun being ferried across the night.

.

.

.

But the disk’s story was just beginning. Its discovery was shrouded in mystery and controversy. The illegal dig damaged its edge, breaking off a piece of the golden arc and scattering some of the golden stars. The artifact vanished into the shadowy world of black-market antiquities, only to resurface years later in Switzerland, where it was finally recovered and authenticated.

Secrets in the Symbols

Scholars and scientists flocked to study the disk. Its bronze came from Central Europe, its gold from distant Cornwall or even Transylvania. The design echoed the Unetice culture, while the spiral bracelets found with it resembled those of Scandinavia and Ireland. The disk’s very existence suggested a network of trade, knowledge, and shared myth stretching across the continent.

The Nebra Disk was more than art—it was a tool. Ancient farmers could use it to track the seasons, guided by the Pleiades, whose rising and setting signaled when to sow and harvest. The disk’s 32 golden stars, the moon and sun, and the carefully placed arcs revealed a sophisticated understanding of celestial cycles. Some believe the disk was even modified over time, its symbols altered to correct for leap months or to hide certain constellations, showing an ongoing relationship between its makers and the night sky.

A Controversial New Age

For years, the Nebra Disk was thought to date to 1600 BC, making it the oldest known depiction of the cosmos. But recent studies by archaeologists from Goethe University and Ludwig-Maximilian University have challenged this, suggesting it may actually be from the Iron Age—a thousand years younger than previously believed. If true, this could upend everything we know about the disk’s origins and purpose, forcing scholars to reconsider its place in the story of human civilization.

The Legacy of the Nebra Sky Disk

Despite the debate, one truth remains: the Nebra Celestial Disk is a masterpiece of ancient science and art. Recognized by UNESCO as a World Documentary Heritage artifact, it stands as proof that even in so-called “barbaric” northern Europe, people gazed upward, tracked the stars, and sought to understand their place in the universe.

Who made the disk, and why did they bury it? Was it a sacred object, a tool for priests, or a gift to the gods? How did it survive for thousands of years, its secrets intact? The answers remain elusive, shrouded in the mists of time.

Yet the Nebra Disk reminds us that the urge to understand the cosmos is as old as humanity itself. Its golden stars still shine, a message from our ancestors: We, too, are made of stardust, forever searching for meaning in the night sky.

News

Thrown from the Bridge, Saved by a Stranger: The Golden Puppy Who Changed Everything

Thrown from the Bridge, Saved by a Stranger: The Golden Puppy Who Changed Everything He was barely a month old—a tiny golden retriever puppy, cream-colored fur still…

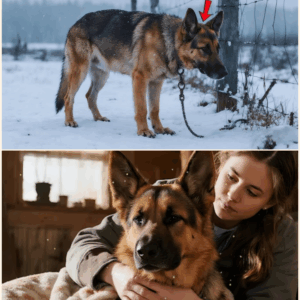

Chained in the Snow: The Emaciated German Shepherd Who Saved a Town—A Tale of Redemption, Courage, and Unbreakable Bonds

Chained in the Snow: The Emaciated German Shepherd Who Saved a Town—A Tale of Redemption, Courage, and Unbreakable Bonds The amber eyes stared up from the snow,…

Dying Dog Hugs Owner in Heartbreaking Farewell, Then Vet Notices Something Strange & Halts Euthanasia at the Last Second!

Dying Dog Hugs Owner in Heartbreaking Farewell, Then Vet Notices Something Strange & Halts Euthanasia at the Last Second! It was supposed to be the end. The…

Everyone Betrayed Him! A Frozen K9 German Shepherd Sat in the Storm—He No Longer Wanted to Survive, Until One Man’s Plea Changed Everything

Everyone Betrayed Him! A Frozen K9 German Shepherd Sat in the Storm—He No Longer Wanted to Survive, Until One Man’s Plea Changed Everything The storm had not…

Girl Had 3 Minutes to Live — Her Dog’s Final Act Made Doctors Question Everything They Knew

Girl Had 3 Minutes to Live — Her Dog’s Final Act Made Doctors Question Everything They Knew A heart monitor screamed into the stillness of the pediatric…

Unbreakable Bond: The Heartwarming Journey of Lily and Bruno, A Girl and Her Dog Healing Together

Unbreakable Bond: The Heartwarming Journey of Lily and Bruno, A Girl and Her Dog Healing Together The shelter was quiet that morning, the kind of quiet that…

End of content

No more pages to load